Friday, July 24, 2015

The Man Who Cried I Am by John A. Williams

Another neglected novel whose author was once mentioned in the same breath as Ellison and Baldwin is The Man Who Cried I Am by John A. Williams, which I began to read shortly after seeing John A. Williams's obituary this month in the NYT, here:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/art...

Like No No Boy, The Man Who Cried I Am hit way too close to the bone to be embraced by white readers in its time, and it is now out of print. Reviews of the novel and of Williams at the height of his career as a novelist, often use the term "angry" to describe both Williams and his work. The "angry black man" label is an all too familiar way that authors become sidelined or deflected from their personal truths by a predominantly white critical reading audience. The critical reception of The Man Who Cried I Am reminds me of the intense scrutiny Ta-Nehisi Coates is receiving from white critics, after the publication of his most recent book, Between the World and Me. In critical reviews of the book, Coates's straight words about his personal experience living as a black man in America are taken somehow as offensive to whites, a feeling that in turn leads to a preachier-than-usual David Brooks scolding Coates in Brooks's July 17 2015 New York Times column:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/17/opi...

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

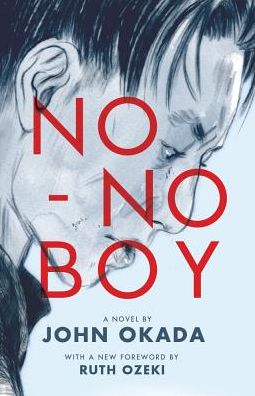

No-No Boy by John Okada

No-No Boy was searingly wrong for its time: in 1956 John Okada wrote a novel about a Japanese American man who went to prison instead of fighting for a country that had sent his family to an internment camp. It was a time when white readers weren't ready to read the truth, and when Japanese-Americans were trying to move on. This novel was just reprinted last year by U Washington Press, with a foreword by Ruth Ozeki--it's worth getting a copy of the new edition just to read her essay about Okada and about the immediate post-WWII realities of Japanese American life. As Ozeki writes in her foreword, Ichiro's "obsessive, tormented" voice subverts Japanese postwar "model-minority" stereotypes, showing a fractured community and one man's "threnody of guilt, rage, and blame as he tries to negotiate his reentry into a shattered world."

I was expecting something polemical when I picked up this novel, and I discovered something far more subtle. The characters are complicated in interesting ways. I expected Ichiro, the titular No No Boy, to be righteous, a conscientious objector, to have a strong and (from my vantage point of 2015) completely defensible reason for refusing to swear loyalty to the United States or to enlist in the US armed forces when at the same time his people were being shipped off to internment camps.

Not at all. The novel is simply told, but never simple. Instead, the protagonist, Ichiro, is full of shame and self-doubt about his decision to refuse to swear a loyalty oath to the U.S. He wishes he could change his mind and take back the last two years, not because he spent them in prison, but because now he doesn't know who he is any longer. He envies friends who have come home wounded from the war; he even envies the war dead, even though their sacrifices have not given their families any more acceptance, and have not shielded them from race hatred at home.

Along with Ichiro, Okada introduces a host of other characters who each reflect a reasonable response to the prejudice and hardships faced by Japanese Americans in the 50's. One of my many favorites is Ichiro's mother, an unabashed Japanese nationalist, a woman who thinks any news about Japanese defeat must be U.S. war propaganda, and who rejects even the letters from her own family members in Japan as false.

Okada's writing has a hard-boiled feel that reminded me of From Here to Eternity by James Jones, which was published just a few years prior to No No Boy. The themes of the novel anticipate the turmoil of the Viet Nam war to follow, when men of a certain age found themselves divided into those who fought, and those who fought the draft. The novel should be read more widely not only as literature but as a fictional testament to the era in which it was written.

Thursday, July 2, 2015

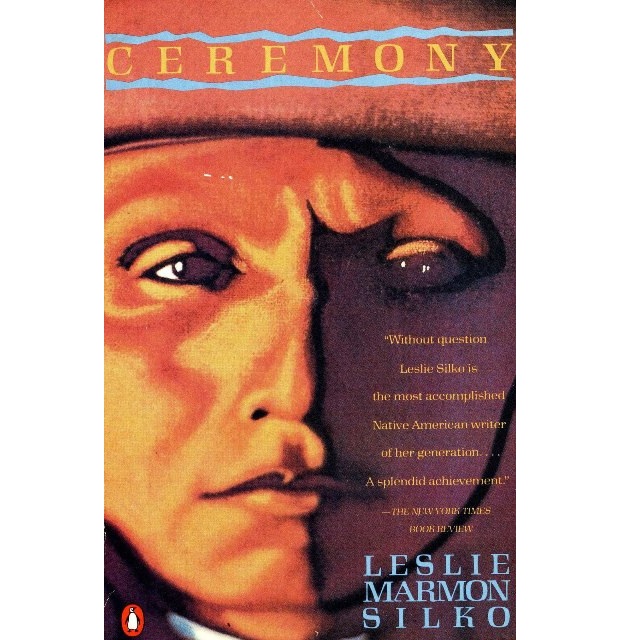

Ceremony, published 1977 by Leslie Marmon Silko

I'm not sure how this novel works, but it does, and beautifully. The same actions and perceptions, throughout the novel, can be taken as signs of mental illness, or signs of mental clarity. Time sequence is broken over and over again in the novel, and yet the movement of the story from beginning to end feels as propulsive and climactic as any linear story. The language feels simple and declarative at first, until I realize that it's highly elevated, to the extent that it resembles poetry--and then it becomes actual poetry on the page. Characters seem simultaneously real and mythological. There are no sharp edges between the characters, either--rather than having any sense of autonomous 'self' they are defined instead by their relationship to one another. What is real and not-real is likewise not sharply defined. Dream bleeds into memory into a fictive reality and back into dream. I didn't feel this novel was written to explain something to me. I felt instead that Silko wrote exactly and uniquely to her purpose. She wrote something entirely new. I've never read anything like it.

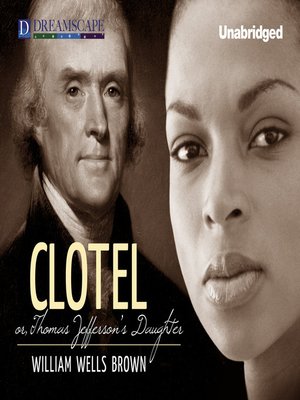

Clotel or The President's Daughter, published 1853 by William Wells Brown

There is something audacious and revelatory about Brown's novel. The first time I came to the sentence where Brown defines his protagonist, Clotel, to be the daughter of Thomas Jefferson, I felt the boldness of that declaration, and the truth of it, and was amazed to realize that it was known in 1853 that Jefferson had children who were slaves, whom he never acknowledged, much less freed. The novel is not a novel in the strictest sense since much of it seems culled from the news of the mid-1850's, and then re-enacted with fictional characters, something like a History Channel documentary will use scenes with actors in their documentaries to portray true events. Each short chapter reads as an episode culled from the news that was contemporary to the novel's publication. The use of fiction to portray real events is done very skillfully here, for example in a scene where the hypocrisy of a white slaveowner reading only those portions of the bible to his slaves that support their bondage is fully revealed, as well as the slaves' full understanding of that hypocrisy. Or when a white mistress comprehends for the first time that a slave's child looks like her husband. The discomfort of both white slaveowners and their darker-skinned slaves at the very existence of light- or white-skinned slaves is difficult to read about, but feels true as well. There are scenes written with great compassion, and sometimes with great brutality, of how slaves tried to escape, and how they were captured and punished for their attempt to escape. Heartbreaking, wrenching, revealing...amazing, especially if as a reader you can let go of the expectations you might have of what a "Novel" is meant to be, and read this instead as a part-indictment, part-historical re-enactment of human lives in the most desperate circumstances.

The Heroic Slave, published 1852 by Frederick Douglass

In The Heroic Slave, his only work of fiction, Douglass feels as if he is searching for a way to use fiction for the purpose of witnessing the truths of enslaved people. He writes scenes that feel like they're from a stage play. The characters speak in lengthy soliloquies. There is nothing real about the encounters between characters. Coincidence plays a high part in plot movement. In spite of all these qualities The Heroic Slave is a moving read. Douglass's dignity and outrage both combine to elevate the language to an eloquence that marks all his writing. But I could almost feel Douglass's growing frustration with the constraints of fiction as he wrote. Because by writing "fiction" he is by definition writing something "not true," his writing about the horrors of slavery sometimes grows more insistent and melodramatic. I believe he discovered even as he wrote this book that fiction a less useful means for him to expose to readers the truth about slavery, and The Heroic Slave remained his only fictional work.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)