Tuesday, July 21, 2015

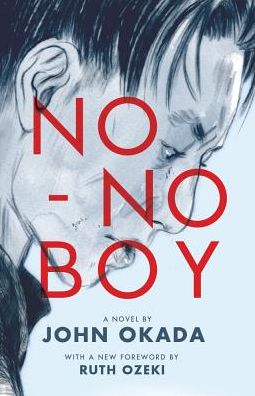

No-No Boy by John Okada

No-No Boy was searingly wrong for its time: in 1956 John Okada wrote a novel about a Japanese American man who went to prison instead of fighting for a country that had sent his family to an internment camp. It was a time when white readers weren't ready to read the truth, and when Japanese-Americans were trying to move on. This novel was just reprinted last year by U Washington Press, with a foreword by Ruth Ozeki--it's worth getting a copy of the new edition just to read her essay about Okada and about the immediate post-WWII realities of Japanese American life. As Ozeki writes in her foreword, Ichiro's "obsessive, tormented" voice subverts Japanese postwar "model-minority" stereotypes, showing a fractured community and one man's "threnody of guilt, rage, and blame as he tries to negotiate his reentry into a shattered world."

I was expecting something polemical when I picked up this novel, and I discovered something far more subtle. The characters are complicated in interesting ways. I expected Ichiro, the titular No No Boy, to be righteous, a conscientious objector, to have a strong and (from my vantage point of 2015) completely defensible reason for refusing to swear loyalty to the United States or to enlist in the US armed forces when at the same time his people were being shipped off to internment camps.

Not at all. The novel is simply told, but never simple. Instead, the protagonist, Ichiro, is full of shame and self-doubt about his decision to refuse to swear a loyalty oath to the U.S. He wishes he could change his mind and take back the last two years, not because he spent them in prison, but because now he doesn't know who he is any longer. He envies friends who have come home wounded from the war; he even envies the war dead, even though their sacrifices have not given their families any more acceptance, and have not shielded them from race hatred at home.

Along with Ichiro, Okada introduces a host of other characters who each reflect a reasonable response to the prejudice and hardships faced by Japanese Americans in the 50's. One of my many favorites is Ichiro's mother, an unabashed Japanese nationalist, a woman who thinks any news about Japanese defeat must be U.S. war propaganda, and who rejects even the letters from her own family members in Japan as false.

Okada's writing has a hard-boiled feel that reminded me of From Here to Eternity by James Jones, which was published just a few years prior to No No Boy. The themes of the novel anticipate the turmoil of the Viet Nam war to follow, when men of a certain age found themselves divided into those who fought, and those who fought the draft. The novel should be read more widely not only as literature but as a fictional testament to the era in which it was written.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment